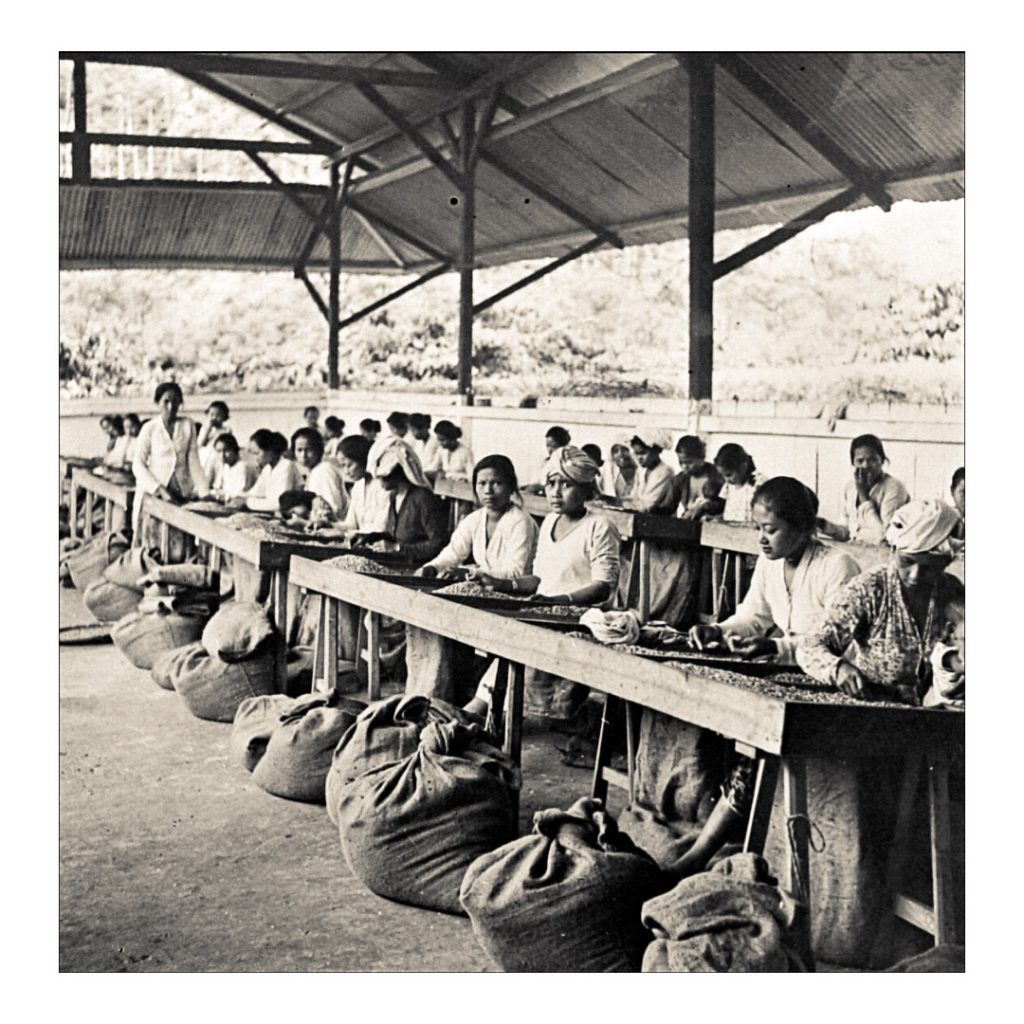

Sorting coffee in West Sumatra, 1941. The woman in the turban seems unhappy; her gaze commands attention. This photograph captures the end of a difficult era — and the beginning of a turbulent decade. Life for the inhabitants of Sumatra under Dutch rule had been hard, and the coming years (and decades) would be particularly tumultuous.

A few months after this photo was taken, the Japanese occupied Sumatra. Coffee production fell by more than 90 percent during the Japanese occupation, as the Japanese uprooted many replanted many coffee farms in food crops, industrial crops, or tea. One author noted that, for coffee farming in the Dutch East Indies, the Japanese occupation was like a second invasion of Hemileia vastatrix, the crop disease that had dedicated the island’s arabica farms in the late nineteenth century (Di Fulvio 1947, 307). After the Japanese surrender in 1945, Indonesian nationalists fought a (successful) war of independence against the Dutch, who had attempted to regain control of their former colony.

In the following decades, the Indonesian coffee economy slowly recovered. The colonial coffee estates have disappeared. Now, most of Indonesia’s coffee is grown on small farms of two hectares or less; about 90 percent of this is robusta. As of 2018/19 Indonesia is the world’s fourth-largest coffee producer, after Brazil, Viet Nam, and Colombia.